Last night I dreamed I went to Steve Jobs’s memorial service, at his house, and comforted his wife. The house was smaller than likely and his wife was lovely. His kids weren’t around, though. Then, in dream logic, I was at a version of my childhood home, and my mother was hosting a women’s luncheon (something she’d never done) and Steve Jobs’s wife was attending. The lunch was in part being held to comfort her. I walked in with an armful of long baguettes, barely hanging on to the loaves going every which way, and gave her the best, freshest one, even though I’d already taken a few bites out of it.

I’ve never been so saddened by a public figure’s death. The only one who comes close is Princess Diana, because I was so in love with her in my youth and got up at three in the morning with my grandmother to watch what I thought at the time was an incredibly romantic wedding. But now Diana doesn’t even compare. With Diana, I lost a childhood crush. With Steve Jobs, I lost someone who, in some surrogate way, has been with me and helped define me through adulthood.

I knew someone who had what must have been a Macintosh 128K my senior year of high school and marveled at how compact it was but teased him for using it and swore I’d never transition to a computer. My father had, against my mother’s wishes, bought a computer when I was in junior high, and it did no more than gather dust, just as my mother had predicted (actually, I was able to make “Jen + Jon” repeat across the screen endlessly, my crush at the time, so perhaps it wasn’t a complete loss).

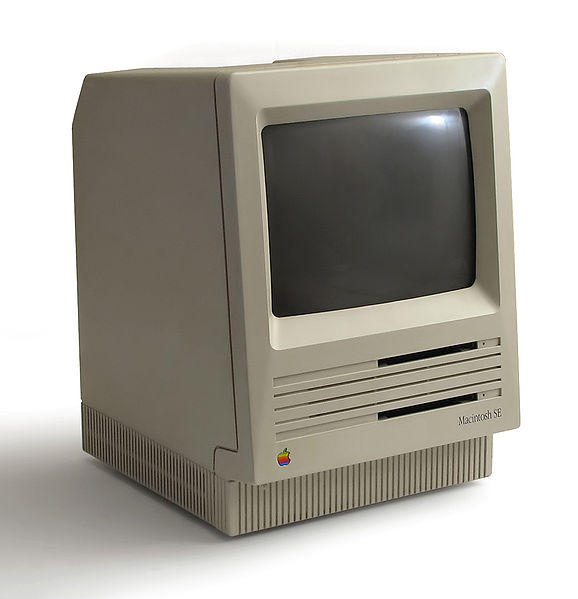

When it came time for me to leave for college in the fall of 1987, my father offered to buy me a computer. Again I said no, I’d never use such an outlandish thing. I’d stick to the typewriter, thank you very much. By November I’d changed my tune as I realized how efficient the University of Michigan computer labs, all stocked with Macintosh SEs, were. It was a steep learning curve, and for a while I used it only as a typewriter with memory, writing my papers by hand then inputting them into the computer merely for presentation. I asked my father if his offer of a computer purchase was still good, and for some reason he said no. My grandmother offered to foot the bill, and at the beginning of my sophomore year, in 1988, I was the proud owner of my first computer (and dot-matrix printer), purchased through the school, each one delivered to students on the same day, a Macintosh SE. My first introduction to fonts, the Mac allowed me to make a cover page for a freshman-year paper on Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra titled something to the effect of “Frustrations, Intellectualizations, Defenestrations, . . . and Zarathustrations,” with every “-ation” in a different font, using every one in the system. I thought it was glorious.

I’ve never owned or worked on a non-Macintosh computer other than checking email on a friend or relative’s PC while traveling, etc. I learned over time to compose on the computer rather than merely typing what I’d handwritten and made the transition to constant revision rather than first draft, revision, second draft, etc., one of the innovations (and downfalls) of word processing and desktop publishing.

Much has been said about Apple’s ability to cultivate rabidly loyal customers for whom their Macintosh, and later their multi-device Apple affiliation, represents far more than the selection of a tool. Apple was to PC as Democrat was to Republican. PCs were selected by default, Apples by choice. Apples were artists, PCs were businesspeople and drones. I was an unwitting brand evangelist for Apple from the beginning, scoffing at and pitying those who’d actively opted for PC or who, worse, didn’t know any better. My card-carrying Apple pride translated into what must have been annoying electronic jingoism.

During Steve Jobs’s years away from Apple, when Apple briefly licensed their operating system to other computer manufacturers (because that had always been the Beta/VHS reasoning behind Microsoft’s supremacy, that Mac had been too selfish, too insular, too un-market-friendly), I owned a generic Mac. It wasn’t as good, and I’ll leave it at that. We Apple lovers talked about the possibility of Macs disappearing entirely, a better product with worse business acumen. When Jobs came back, exciting stuff started to come out of Apple again, and soon came the iPod and iPhone and iPad revolution, the one that has me never more than a few feet away from an Apple device.

At Knock Knock, the business side of the office works on PCs and the creatives work on Macs. While now there are PC versions of the kinds of creative software we use, back in the day, when I first entered publishing in the early- to mid-1990s and experienced the first implementation of desktop publishing, witnessing the departure of paste-up boards and linotype, Macs were the only option for us. The Knock Knock creative group, I would guess, secretly feels a little sorry for the PC people with their g-drives and control keys and susceptibility to viruses. Not to mention that their computers just aren’t pretty.

Over the last few years of Apple devices, I’ve found myself thinking about and projecting onto Steve Jobs as I use the things. “How does Steve Jobs put up with the iPhone’s autocorrect?” I ask inside my head. “Surely it must bother him at least as much as it bothers me.” This has always been so different from my frustrations with Microsoft, with software flaws that are so obviously the result of greed (fixing what isn’t broke and overcomplicating just to release a new version) and poor management and not really caring about the user. When I talk to Bill Gates in my head, it’s not very nice. When I criticize Steve Jobs’s choices, it’s debating with a mentor.

And who ever knew that I’d become a businessperson? Those are the kinds of people who use PCs, right? I had something else to admire about Steve Jobs—his inspiration, and most of us do use that word too lightly, as the leader of a company with vision, his gorgeous monarchy. The fact that he yelled at employees and made them cry helped me feel a little better about my own shortcomings—even his imperfections comforted me. He cared about creativity and innovation and ideas rather than wardrobe and conspicuous consumption.

As he got sicker and his emaciation became evident, I imagined his body as a carrier for his brain and somehow couldn’t conceive of his death. Surely they would find a way to keep so important a brain alive and, like Steven Hawkings, his physical representation would atrophy into a flawed vessel for that magnificent brain whose ideas and genius we’d want for a few more decades.

I still identify with Apple and Mac as I identify as a liberal, as a humanist, as an aesthete, as some of the more important pieces of who I am. I can’t think of another brand that does that. I loved watching Jobs’s efforts and struggles writ large, his somewhat unpolished, unfiltered public persona, his impatience for things that didn’t truly matter. I love that he was a renaissance man when such goes unrewarded today and is thus in short supply.

Steve Jobs was to me, as it’s apparent he was to many people, something personal. With his family’s sentence “Steve died peacefully today surrounded by his family,” all I could think about were the last days of my mother’s life when she died at home of breast cancer at the age of forty-nine in 1991. I knew what his family had experienced in tending him closely, helping to usher him to the next adventure. I loved that in the end he had not only the billions and the fame and the success but also the intimates to retreat to, who cared for him and witnessed his private human ending. In the end, this is what made me cry when I learned of his death.